“Once a low-risk woman has a cesarean delivery, she will never have a low-risk pregnancy again.”

The origin of this series of posts about avoiding Cesarean birth dates back 9 years. The purpose of writing about avoiding Cesareans is still the same, there were too many surgical births then and there are still are today. The difference is that in the past 9 years, my determination to tip the scale back toward normal, natural birth has multiplied exponentially. I live in New Jersey, where cesarean birth happens almost as often as vaginal birth. We have so many cesareans in New Jersey that our state has a specialized Center for Abnormal Placentation. Abnormal implantation of the placenta is when the placenta grows into the actual uterus and even beyond the uterus. rather than just the uterine lining (endometrium). This is most commonly caused by cesarean surgeries which can cause significant damage to the lining of the uterus. Placenta accreta, increta and percreta were once extremely rare occurrences but now because of the increase in primary cesareans and repeat cesareans, they happen commonly enough in New Jersey to support a special center.

“Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Hackensack University Medical Center has been developing a program to serve the growing need for the comprehensive care of patients with placenta accreta. Given the significant increase in births by cesarean section each year, which directly contribute to problems with placental formation in subsequent pregnancies, the incidence of placenta accreta will continue to rise, as will morbidity and mortality rates for pregnant women“( Source).

History of Cesarean Section in the U.S.

Before discussing how a woman can work to avoid a cesarean, cesarean section should be defined from a contemporary point of view. The first Cesarean deliveries were performed to attempt to save the baby’s life because the laboring mother was dying or had died. Not until the advent of hospital birth with antibiotics, anti-hemorrhage drugs, improved surgical techniques and regional anesthesia, did cesarean section become a truly viable delivery method. In 1970, our national average for cesarean deliveries was 5%, by 1987 it was 24% and by 2013 the United States was at 32% or approximately 1/3 of all births.

The culture has changed since 1970 and these changes result in more surgical birth. In 1970, women were encouraged to gain less weight in pregnancy, smoking in pregnancy was common, physicians were skilled in delivering babies with forceps, breech babies and twins were generally delivered vaginally and the culture as a whole valued vaginal birth and feared cesarean. Fast forward almost 50 years and many things have changed. C-section has become so common that no one is surprised when it happens. Women are delaying childbearing and as a result, they enter pregnancy with more medical problems like diabetes and hypertension (which complicate pregnancy). They have a greater need for infertility treatments which can result in more risky pregnancies like multiple gestation. Obesity is much more common now and can complicate pregnancy as well.

Less Recognized Reasons for Cesarean:

- Medical-led view of pregnancy and birth, leading to higher rates of interventions

- Fear of birth and labor pain

- Fear of medical litigation

- Belief that c-section prevents trauma and damage to the pelvic floor

- Belief that c-section is less traumatic to the baby

- Convenience to care provider and mother

- Low tolerance of anything less than the perfect birth outcome

- Cultural considerations, such as birth date being lucky for future or destiny

Source: Sam McCulloch Dip CBEd in Birth

The need for surgical birth HAS increased over the years. There are birth outcomes that are now considered unacceptable by most childbearing families and their providers because surgical intervention is relatively safe and very available. A cesarean section is major abdominal surgery and should be avoided whenever safely possible.

Modes of Delivering a Baby

A surgical birth is one of the 3 ways that a baby can be born: Spontaneous vaginal birth, operative vaginal birth and surgical abdominal delivery. All modes of delivery have advantages and disadvantages but it is undisputed that vaginal birth is the gold standard. The typical surgical birth has the woman entering the operating room alone. Her partner waits for the operating room to be set-up and the regional anesthesia like a Spinal block to be completed before they can come into the operating room. The surgery takes about 45 minutes with the baby being born in the first 10 – 15 minutes and the repair taking the remaining time during which the baby and partner are frequently in the nursery. The baby is usually returned to the mother to breastfeed and bond in the recovery room. Following most cesareans, a urinary catheter is in place for 24 hours, the IV remains for at least 24 hours, the woman stays in bed for at least 12-18 hours after surgery and in the hospital a day or 2 longer than with vaginal birth.

Some cesarean sections are scheduled to occur prior to the onset of labor because labor itself is considered dangerous like in the case of a diagnosis of complete placenta previa (placenta implanted directly over the cervical opening). The labor could cause the baby to be in danger like when the baby is lying sideways (transverse) in the uterus which presents the danger of a cord prolapse when the water breaks. Other cesareans are scheduled because the provider is trying to mitigate the risk of the vaginal birth like a case where the baby is estimated to be large or the baby is breech. Many cesareans happen during labor because the labor does not progress. Some happen because of fetal stress in labor and others because the mother is not medically stable. Women choose cesarean sometimes because of personal reasons. No matter the reason, there are times when a surgical birth is a good idea and some when it is not.

A Cascade of Interventions

I am interviewed by women looking for Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC) every week. In so many of their stories, I hear their frustration with the assembly-line type care they found themselves receiving. The women had no idea how little their provider and hospital staff knew about promoting normal birth. Even if these women were familiar with the concept of the “cascade of interventions”, they were shocked at how easily they were caught up in it. Then, when it was all said and done, most women express their disappointment in the overall experience. They were expecting more respect and more involvement in decision-making but came to find out that EVERYONE at the hospital knew better about what she and her baby needed than she did. Instead of growing stronger as a woman and mother, they left for home feeling a little, or even a lot, beaten up by the whole process. Most women are happy about or at least resigned to their surgical birth immediately postpartum because it is hard to be unhappy with the long-anticipated babe in their arms. But I do know as time goes by, women begin to question more and more the reasons for their surgical delivery. In the moment, it may have seemed easier to just go ahead and get the baby out but later they wonder what would have happened if they had pressed on for a little or even a lot longer.

Our clients who work very hard for their vaginal birth are not always immediately thrilled with the amount of hard work it took to deliver their baby, especially during the recovery time. But ultimately, women stop focusing on the pain and the fatigue and remember feeling powerful and accomplished for doing something as challenging as childbirth. Whether a woman “liked” birth or not is not necessarily as important as whether she was treated with respect in the decision-making. And women rarely question a cesarean for which they worked very hard and in which they shared the decision-making.

I sense that women have no idea of the risks surrounding a surgical versus vaginal birth. Cultural fear of labor pain is so pervasive that women will go to great lengths to avoid the pain. Unfortunately, the mothers are not given informed consent about impact of epidural anesthesia on the progress of labor and increased risks of fetal distress, forceps or vacuum delivery or cesarean section. But even knowing the risks of regional anesthesia, many women will still make the choice to avoid pain because our culture also believes that cesarean and vaginal birth are equal. Let me be clear. The Cesarean delivery is no more equal to vaginal birth than formula is equal to breastmilk. And not nearly as safe.

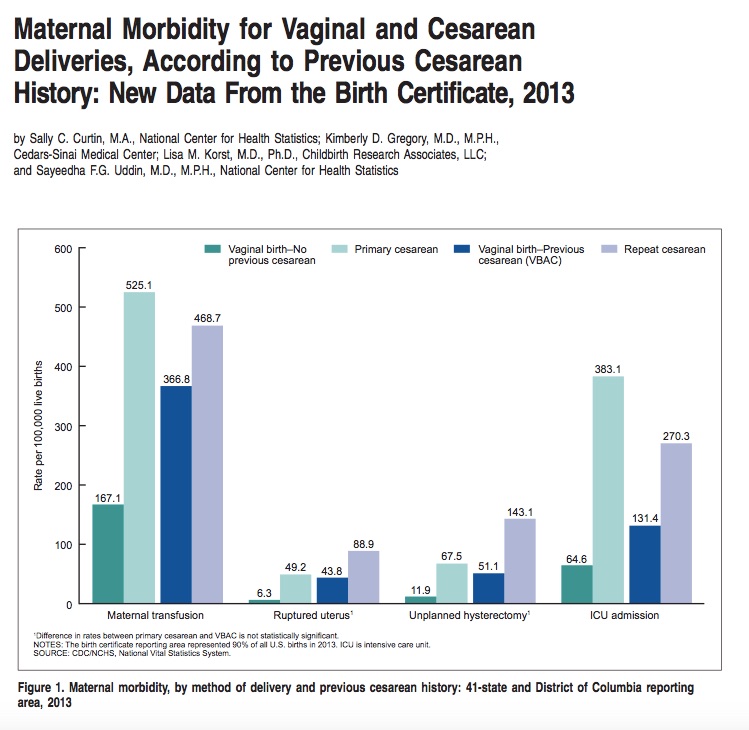

Risks Associated with Cesarean Delivery

1. Increased Risk of Infection

In this age of laparoscopic surgery, cesarean incisions are some of the largest made in the human body. Laparoscopes were invented because the larger the incision, the greater the risk of infection. Babies are bigger than gallbladders and appendixes and thus require a large incision to be born.

I hope that all people understand the evolution of “superbugs”. As bacteria are exposed to antibiotics, they can potentially mutate to a point where almost no antibiotics will work against them. This is what happened to a strain of staph aureus – we now have something called MRSA – methicillin resistant staph aureus. It is generally hospital-acquired and of course, a hospital is where cesareans are performed.

Most cases of overwhelming infection related to childbirth result from a surgical birth, not a vaginal birth. The vagina is designed to resist the ascension of bacteria to the cervix. The inside of the abdomen is not.

2. Increased Risk of Hemorrhage

Again, the risk of overwhelming, life-threatening blood loss is associated with cesarean, not vaginal birth.

3. Increased Risk of Hysterectomy

Sometimes the only way to stop bleeding is to remove the uterus.

4. Increased Risk of Postpartum Pain

Certainly, women can have significant pain following a vaginal birth but statistically, women have more pain following a cesarean.

5. Less immediate bonding with baby

Even in the situation where a baby remains in the OR after he has been born, he is still almost never greeted by his mother immediately. The baby is greeted by the surgeon and then the nursery staff before being handed to his parents. Even this amount of separation can detrimental to the mother-baby bond.

6. Less successful breastfeeding

7. Increased risk of postpartum depression

8. Each Successive Cesarean Becomes Riskier; Posing Risks for Higher Morbidity and Mortality to Both Mother and Baby.

9. Limited Family Size

Because of the risk of abnormal placental implantation and significant surgical complications after repeated cesarean sections, most women are advised to stop having children after 3 surgical births. Understanding that many women do not wish more than 3 children, this could be viewed as a non-issue. It just seems that a woman should be able to choose her family size-not her obstetrician.

Labor is good for the baby-especially when allowed to start on its own and progress naturally. The onset of labor is signaled by the baby, which means that the baby is likely ready for extra-uterine life or if not ready, that it expects the outside world will be more favorable than its intrauterine world. This is the reason babies exposed to toxins like cigarettes, illegal drugs or poor nutrition will choose to be born early.

The bowel flora of a vaginally-born baby is completely different than that of a cesarean baby. The vagina helps to colonize the baby’s gut with friendly bacteria. This is the first part of a healthy immune system which will dictate health for this person throughout their lifetime.

Babies born vaginally transition more easily. Again, the fact that it takes a section baby a little longer to breathe normally and maintain its body temperature independently, means it is more likely that the baby will be separated from its mother for extended periods of formative time. The mother-infant bond is the most significant relationship in a human’s life. The relationship is a biologic imperative, meaning that survival is dependent on the mother and baby attaching to one another. But it is even more than just surviving, it is supporting optimal mental and physical health for both parties which should be the goal of both families and health care providers.

Listen Carefully:

“Once a low-risk woman has a cesarean delivery, she will never have a low-risk pregnancy again.”

My experience is that women are not as concerned about this low-risk status before their section as they are afterward. Motherhood has a way of making women more opinionated about a wide range of childbearing and parenting decisions. They often begin to research their options for their best birth with their SECOND pregnancy and are truly distraught to find out that their Cesarean birth eliminates many of their options. The search for the healthiest birth must begin before the first pregnancy so women can position themselves for the healthiest birth for themselves and ALL of their children.

Delivering babies vaginally must be a priority for women, Midwives and Physicians, medical centers, regulating bodies and our culture as a whole. Avoiding the first cesarean is a huge agenda item for both the American College of OB/GYN and American College of Nurse-Midwives. Very simple changes in a woman’s pregnancy care and birth management can improve outcomes for mothers and babies dramatically. As it stands today, women do not have the luxury of relying on our healthcare system to give them the best chance for a low-risk delivery. They must be their own advocates. This blog series is intended to equip families with the information about avoiding cesarean and achieving a positive birth experience, no matter the route the baby ultimately takes.

The next post in the Avoiding Cesarean Series addresses how to create a Preconception Birth Plan.

4 Easy Ways to Improve Sperm Health

4 Easy Ways to Improve Sperm Health